BODY CONTOURING IMPLANTS

When it comes to calf implants and calf anatomy, what are considered “good anatomical proportions?” And, how is this determined?

Introduction to Calf Augmentation—

Calf implants are typically used for reshaping the lower leg region—specifically the anatomical proportions of the medial (inside) and lateral (outside) Gastrocnemius and Soleus muscles (commonly called the calf)—to the upper leg region (quadriceps or thigh).

There are two common surgical approaches to calf augmentation. One involves placing the calf implant under the deep fascia (submuscular technique, or under the aponeurosis); the other procedure places the implant just under the dermis, within the fascia of the muscle (subfascial technique). This report will examine the two methods of calf augmentation, discuss the implant construction and design, delve briefly into the surgical techniques involved, and discuss the results and expectations from each method.

To begin, it’s important to understand the basis, or rationale for calf augmentation. It’s performed for both aesthetic and reconstructive reasons. From an aesthetic perspective, both fashion and lifestyle changes in Western Society have made calf augmentation more desirable, particularly among women, because of an emphasis on shapely legs due to dress and shoe fashions. Simply said, in modern western cultures it’s considered a physical attribute to have attractive, well-defined legs. As well, there is an increasing demand for calf implants among both male and female athletes who desire additional definition in the calf area, which can’t be achieved by only muscle mass increases.

In reconstructive applications, calf augmentation is a vital and necessary method of rebuilding the lower section of the leg due to congenital disability—particularly in Poliomyelitis (Polio), which is a leading cause of calf deformity. Other genetic disorders can affect calf development as well, including Spina Bifida and Club Foot. In each case, an aesthetic and/or reconstructive surgeon will evaluate the proportions of the calf in relation to the overall anatomical ratio of the leg and musculature.

So, when it comes to calf implants and calf anatomy, what are considered “good anatomical proportions?” And, how is this determined?

The discussion of anatomical proportions begins with an understanding that the science of aesthetics and interpretation of beauty is one that varies demonstrably from one individual to another. What may be considered “attractive” to one person may not be considered so in another. Hence, aesthetic beauty is not considered a cognitive function. That means, one doesn’t “think” about what makes a person beautiful/attractive to them—they only “react” to physical characteristics. Because of this, the interpretation of what one thinks is beautiful, or attractive, is thought to be resident in the subconscious, or limbic cranial system. The term Limbus, or Limbic, in medical terminology is used to describe a border region. In the brain, it’s those structures including the hippocampus, amygdala (amygdaloid body), dentate gyrus, cingulate gyrus, gyrus fornicatus, the archicortex, septal area and others. This area of the brain is set in motion by external influences (stimuli—such as seeing an attractive man, or woman) creating either subliminal or self-aware motivational behavior (desires/wants/arousal)—which in turn affects the endocrine glands and autonomic nervous system (sweat glands, heart rate, etc.). A very simplistic example of this would be if you saw a visual representation that you thought was attractive in some way . . . this information stimulates a desire, which in turn initiates physical indicators such as making your heart beat faster, or getting excited, etc. It’s a primal region of the brain, and as such, seems to be the determining force behind one’s desires for a particular type of man, or woman.

Is beauty an attribute really in the eye of the beholder? Most definitely . . . yes.

That’s because there are so many different interpretations of beauty. As well, there are also some defined similarities. These commonalities in aesthetic beauty were first studied centuries ago by a number of people . . . most often those involved with architectural or artistic occupations. Their goal was to determine what good human proportions actually were, from those who were thought to be attractive by many people. It was largely done so they could reproduce these appearances in artwork and designs; a matter of good business practices, rather than biology or medicine. Only later did mathematicians, engineers and medical scientists got involved in refining these views and calculations. However, much of what was initially determined still is used today.

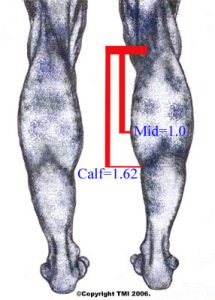

As it relates to the lower leg, anatomical proportions considered to be aesthetically pleasing were, of late, calculated by Dr. R. M. Ricketts who determined these dimensions to be mathematical ratios of X, Y, Z (width, height, depth), as well as angular proportions of the human body, to define what is termed the “golden proportion” (1:1.618). Ricketts was not the first determine this ratio, as it’s been deeded to an Italian mathematician, Filius Bonacci, who first recorded this information back in the 12th century. For calves, the most aesthetically pleasing dimension, or proportion, is merely a matter of measurement. In simple terms, if one measures the distance from the knee to the widest medial point of the calf muscle, then multiples this distance by 1.6, the proper proportions as stated by the golden proportion ratio, the entire length of the gastrocnemius muscle (calf muscle) must be at least 1.6 times the length of this upper value, to create proper calf symmetry. Circumference varies, according to length of entire muscle, but generally it has been found to be approximately 12-13 inches in size for most women.

Where Calf Implants Are Inserted—

Once a need for calf implants is determined, they are placed either; 1) subfascially, or; 2) submuscularly—underneath the aponeurosis (subaponeurotically)—flat fibrous sheets of connective tissue that typically attach the muscles that make up the calf—gastrocnemius and soleus muscles—to the bone. More commonly, calf implants are placed subfascially (just below the fascial plane), but many of the best results are obtained by placing the implant in the submuscular plane—deeply within the muscle.

1. Subfascial placement of the calf implant is generally performed more often because the procedure is less dissection-intensive, less difficult, and results in generally faster recovery times with patients reporting less pain. However, subfascial implant placement can sometimes result in calf implant movement (drift or rotation), and/or result in the patient being able to feel the perimeter edges of the implant afterwards, because they are usually harder than the nearby muscle and not enough tissue covers the implant itself. As well, sometimes the desired effect isn’t aesthetically as pleasing as the submuscular method because the implant itself tends to define the final shape of the calf region, rather than the muscle tissue. This is true with either silicone-gel or solid silicone calf implants. Subfascial implantation also requires more attention to the placement of the implant, which can become difficult when trying to reach the most distal region (distant from the center) of the crural pocket where the implant is placed.

2. Submuscular (subaponeurotically) placement is considered a more difficult procedure and requires more surgical skill as the operation delves deeply into tissues. Generally, however, the results are better because the implant is placed more securely and accurately within the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles (within deeper fascia tissues), allowing for more aesthetic placement of the implant. Also, it’s been observed that submuscular implantation can result in a more natural calf shape and feel because the actual muscles of the calf cover the implant completely. However, this method of calf augmentation generally requires a few more days of patient recovery time and more discomfort until the deep tissue trauma begins to heal. Another benefit of submuscular placement is that since this procedure is more involved it also allows for greater control of potential surgical hazards including vascular or nerve damage—incisions are made far away from the junction of the gastrocnemius muscles.

In both methods, however, basic anatomy is favorable for calf augmentation because there are few nerves or blood vessels present in this area, hence little chance of permanent damage. Once the surgeon locates the key sensory nerve (tibial nerve) they can proceed without too much concern, forming the desired implant pockets in the muscle compartments.

Calf Implant Materials & Types—

Both silicone-gel implants and solid silicone implants are available for calf implants. Silicone-gel calf implants sometimes have problems with capsular contracture, although this is much more problematic with breast implants rather than calf implants, while solid silicone implants can leave an edge that can be felt externally if placed too near the surface, as with subfascial calf augmentation.

Silicone-gel filled calf implants usually come in symmetrical a cigar-shaped size with volume ranges from 50-220cc. Many are also available in anatomical sizes (asymmetrical), where the upper portion of the implant is usually larger in volume than the lower section. Most silicone-gel implants have a shell that is composed of silicone elastomers (medically approved grade), and a volumetric gel that is made of cohesive silicone, so it won’t migrate to other areas if the implant is somehow ruptured. Solid-silicone implants, and middle-soft silicone implants come in a variety of styles and because of their solid and semi-solid consistency the surgeon can carve them into custom shapes before implanting to allow for asymmetric muscular development. Anatomical implants (asymmetrical), are best used for body builders who desire a more dramatic look for enhancement of the medial (inside calf) point, or peak. This added volume can give the body builder the “cut” they desire when they can’t achieve additional mass by weight training alone. Normally, most consumers are fitted with symmetrical calf implants because the narrower profile permits a more natural curve in proportion to the upper thigh. Sometimes, depending on the size of the patient’s ankle, circumferential liposuction will also be performed at the close of the procedure to sculpt the areas above the ankles and subcutaneously above the calf muscles to enhance the overall look of the leg.

Aesthetic & Reconstructive Technologies, Inc. (AART), a highly respected, well-known manufacturer of implant technology offers surgeons only the best, most advanced implants for use in their surgical procedures. All of AART’s implants are manufactured out of the highest quality Implant Grade silicones and are engineered to mimic the tissues that they are augmenting or replacing.

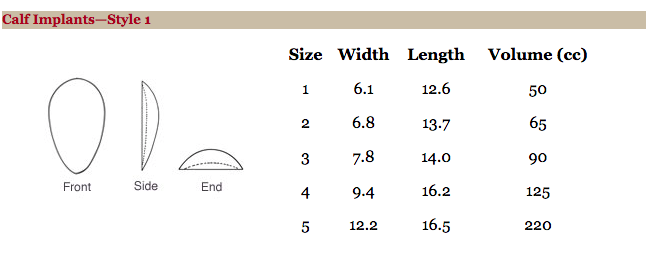

As you might expect, all calf implants are sterilized before placement. Each Style and size of calf implant has varying dimensions, and hence, different volumes. Again, the selection of the proper style and size calf implant depends on the desired need, and “look” your surgeon feels is appropriate to achieve the best, most natural appearance.

Custom calf implants, made of solid silicone, can be carved specifically for the individual. Some surgeons, usually those with vast experience in the implant procedure, can modify them as needed with surgical instruments such as a scalpel or scissors before placing them within the muscle plane.

Calf Implants are available in three styles and several sizes. They are available non-sterile and sterile, and are packaged and sold individually. Depending on the patient needs, the doctor may use one or two implants (medial and lateral) in each leg.

Calf Implants—Style 1

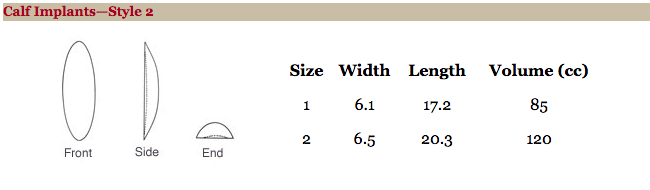

Calf Implants—Style 2

Results & Expectations—

In almost every case, with either method (submuscular or subfascial) of calf augmentation, patients were able to return to normal activities within a few weeks. Body builders sometimes required slightly more time. As well, calf augmentation reports one of the highest levels of satisfaction among patients, with less than four percent (4%) reporting any complications or infection. Some surgeons report even being able to eliminate antibiotic regimes by applying some techniques from breast augmentation, including the use of barrier membranes to prevent contact between the implant and skin. It has also been determined that calf implants and augmentation does not in any way impair the normal function of the calf muscle or calf, and in fact, offers a level of improved self-esteem in those who have had the surgery performed.